In Achebeã¢â‚¬â„¢s Things Fall Apart, What Best Describes the Way Okonkwo Treats His Family?

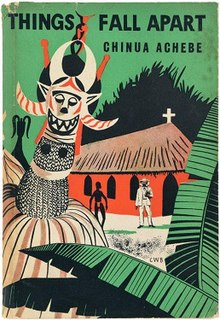

Outset edition | |

| Writer | Chinua Achebe |

|---|---|

| Country | Nigeria |

| Language | English language |

| Publisher | William Heinemann Ltd. |

| Publication date | 1958 |

Things Fall Apart is the debut novel by Nigerian author Chinua Achebe, first published in 1958. It depicts pre-colonial life in the southeastern role of Nigeria and the invasion by Europeans during the tardily 19th century. It is seen as the archetypal modern African novel in English, and ane of the showtime to receive global critical acclaim. It is a staple volume in schools throughout Africa and is widely read and studied in English language-speaking countries effectually the world. The novel was first published in the Britain in 1962 by William Heinemann Ltd, and became the start work published in Heinemann'south African Writers Series.

The novel follows the life of Okonkwo, an Igbo ("Ibo" in the novel) man and local wrestling champion in the fictional Nigerian association of Umuofia. The work is divide into three parts, with the outset describing his family, personal history, and the customs and society of the Igbo, and the second and third sections introducing the influence of European colonialism and Christian missionaries on Okonkwo, his family, and the wider Igbo customs.

Things Fall Apart was followed by a sequel, No Longer at Ease (1960), originally written as the 2nd part of a larger piece of work forth with Pointer of God (1964). Achebe states that his two later novels A Man of the People (1966) and Anthills of the Savannah (1987), while not featuring Okonkwo's descendants, are spiritual successors to the previous novels in chronicling African history.

Plot [edit]

Part i [edit]

The novel's protagonist, Okonkwo, is famous in the villages of Umuofia for being a wrestling champion, defeating a wrestler nicknamed "Amalinze The Cat" (considering he never lands on his back). Okonkwo is strong, hard-working, and strives to show no weakness. He wants to dispel his father Unoka'south tainted legacy of unpaid debts, a neglected married woman and children, and cowardice at the sight of blood. Okonkwo works to build his wealth entirely on his own, as Unoka died a shameful decease and left many unpaid debts. He is as well obsessed with his masculinity, and any slight compromise to this is swiftly destroyed. Equally a effect, he oft beats his wives and children, and is unkind to his neighbours. However, his bulldoze to escape the legacy of his father leads him to exist wealthy, courageous, and powerful amidst the people of his hamlet. He is a leader of his village, having attained a position in his lodge for which he has striven all his life.[1]

Okonkwo is selected by the elders to be the guardian of Ikemefuna, a boy taken by the clan as a peace settlement between Umuofia and another clan after Ikemefuna's father killed an Umuofian woman. The boy lives with Okonkwo's family and Okonkwo grows fond of him, although Okonkwo does not show his fondness so as not to appear weak. The boy looks up to Okonkwo and considers him a second father. The Oracle of Umuofia eventually pronounces that the boy must exist killed. Ezeudu, the oldest man in the village, warns Okonkwo that he should have nothing to do with the murder because it would be like killing his own kid – but to avoid seeming weak and feminine to the other men of the village, Okonkwo disregards the warning from the old man, striking the killing blow himself fifty-fifty as Ikemefuna begs his "father" for protection. For many days later killing Ikemefuna, Okonkwo feels guilty and saddened.

Presently after Ikemefuna's expiry, things brainstorm to go wrong for Okonkwo. He falls into a great depression, as he has been greatly traumatized by the act of murdering his own adopted son. His sickly daughter Ezinma falls unexpectedly ill and it is feared she may die; during a gun salute at Ezeudu'due south funeral, Okonkwo'southward gun accidentally explodes and kills Ezeudu's son. He and his family are exiled to his motherland, the nearby village Mbanta, for seven years to appease the gods he has offended.

Office ii [edit]

While Okonkwo is away in Mbanta, he learns that white men are living in Umuofia with the intent of introducing their faith, Christianity. Every bit the number of converts increases, the foothold of the white people grows and a new government is introduced.[2] The village is forced to respond with either appeasement or resistance to the imposition of the white people'south nascent social club. Okonkwo'south son Nwoye starts getting curious well-nigh the missionaries and the new organized religion. After he is beaten past his father for the last fourth dimension, he decides to leave his family behind and live independently. He wants to be with the missionaries because his beliefs take inverse while being introduced to Christianity past Mr. Brown. In the last year of his exile, Okonkwo instructs his all-time friend Obierika to sell all of his yams and hire ii men to build him two huts so he can have a house to go back to with his family. He also holds a keen feast for his mother's kinsmen, where an elderly attendee bemoans the current state of their tribe and its time to come.

Part 3 [edit]

Returning from exile, Okonkwo finds his village changed by the presence of the white men. Later a convert commits an evil act by unmasking an elderberry as he embodies an bequeathed spirit of the association, the village retaliates by destroying a local Christian church building. In response, the District Commissioner representing the colonial authorities takes Okonkwo and several other native leaders prisoner pending payment of a fine of ii hundred bags of cowries. Despite the District Commissioner's instructions to treat the leaders of Umuofia with respect, the native "court messengers" humiliate them, doing things such as shaving their heads and whipping them. As a issue, the people of Umuofia finally get together for what could exist a nifty insurgence. Okonkwo, a warrior by nature and adamant virtually following Umuofian custom and tradition, despises any form of cowardice and advocates war against the white men. When messengers of the white government effort to cease the meeting, Okonkwo beheads i of them. Because the oversupply allows the other messengers to escape and does not fight alongside Okonkwo, he realizes with despair that the people of Umuofia are non going to fight to protect themselves – his society's response to such a disharmonize, which for so long had been predictable and dictated by tradition, is changing. The District Commissioner Gregory Irwin then comes to Okonkwo'southward house to take him to court, he finds that Okonkwo has hanged himself to avert being tried in a colonial court. Among his own people, Okonkwo'southward actions have tarnished his reputation and status, every bit it is strictly against the teachings of the Igbo to commit suicide. Equally Irwin and his men set to bury Okonkwo, Irwin muses that Okonkwo'southward decease will make an interesting chapter for his written book: "The Pacification of the Primitive Tribes of the Lower Niger."

Characters [edit]

- Okonkwo, the protagonist, has three wives and ten (full) children and becomes a leader of his clan. His father, Unoka, was weak and lazy, and Okonkwo resents him for his weaknesses: he enacts traditional masculinity. Okonkwo strives to brand his style in a culture that traditionally values manliness.

- Ekwefi is Okonkwo'due south second wife. Although she falls in love with Okonkwo after seeing him in a wrestling match, she marries some other man because Okonkwo is too poor to pay her bride cost at that time. Two years later, she runs away to Okonkwo'due south chemical compound one night and later marries him. She receives severe beatings from Okonkwo just like his other wives; but different them, she is known to talk dorsum to Okonkwo.

- Unoka is Okonkwo's father, who defied typical Igbo masculinity past neglecting to abound yams, take care of his wives and children, and pay his debts before he dies.

- Nwoye is Okonkwo's son, about whom Okonkwo worries, fearing that he will become like Unoka. Similar to Unoka, Nwoye does not subscribe to the traditional Igbo view of masculinity being equated to violence; rather, he prefers the stories of his mother. Nwoye connects to Ikemefuna, who presents an alternative to Okonkwo'southward rigid masculinity. He is one of the early converts to Christianity and takes on the Christian name Isaac, an human activity which Okonkwo views as a final betrayal.

- Ikemefuna is a boy from the Mbaino tribe. His father murders the married woman of an Umuofia man, and in the resulting settlement of the matter, Ikemefuma is put into the care of Okonkwo. By the conclusion of Umuofia authorities, Ikemefuna is ultimately killed, an human activity which Okonkwo does not foreclose, and even participates in, lest he seems feminine and weak. Ikemefuna became very close to Nwoye, and Okonkwo's determination to participate in Ikemefuna's expiry takes a cost on Okonkwo's relationship with Nwoye.

- Ezinma is Okonkwo'southward favorite daughter and the only child of his wife Ekwefi. Ezinma, the Crystal Dazzler, is very much the antithesis of a normal woman within the culture and Okonkwo routinely remarks that she would've fabricated a much amend male child than a girl, even wishing that she had been born as ane. Ezinma often contradicts and challenges her male parent, which wins his admiration, affection, and respect. She is very similar to her father, and this is fabricated apparent when she matures into a beautiful young woman who refuses to ally during her family unit'south exile, instead choosing to help her father regain his identify of respect within gild.

- Obierika is Okonkwo's best friend from Umuofia. Unlike Okonkwo, Obierika thinks before he acts and is, therefore, less violent and arrogant than Okonkwo. He is considered the vox of reason in the book, and questions certain parts of their culture, such as the necessity to exile Okonkwo later he unintentionally kills a boy. Obierika's own son, Maduka, is greatly admired by Okonkwo for his wrestling prowess.

- Ogbuefi Ezeudu is one of the elders of Umuofia.

- Mr. Brown is an English missionary who comes to Umuofia. He shows kindness and compassion towards the villagers and makes an effort to sympathise the Igbo beliefs.

- Mr. Smith is another English language missionary sent to Umuofia to supervene upon Mr. Brown after he falls ill. In stark contrast to his predecessor, he remains strict and zealous towards the Africans.

Background [edit]

The championship is a quotation from "The Second Coming", a verse form by West. B. Yeats.

Most of the story takes place in the fictional village of Iguedo, which is in the Umuofia clan. The place name Iguedo is but mentioned three times in the novel. Achebe more frequently uses the name Umuofia to refer to Okonkwo's home village of Iguedo. Umuofia is located west of the actual urban center of Onitsha, on the east bank of the Niger River in Nigeria. The events of the novel unfold in the 1890s.[3] The culture depicted, that of the Igbo people, is like to that of Achebe's birthplace of Ogidi, where Igbo-speaking people lived together in groups of contained villages ruled by titled elders. The customs described in the novel mirror those of the bodily Onitsha people, who lived near Ogidi, and with whom Achebe was familiar.

Inside xl years of the colonization of Nigeria, by the fourth dimension Achebe was born in 1930, the missionaries were well established. He was influenced past Western culture but he refused to change his Igbo name Chinua to Albert. Achebe'southward father Isaiah was among the first to exist converted in Ogidi, around the turn of the century. Isaiah Achebe himself was an orphan raised by his grandfather. His grandfather, far from opposing Isaiah's conversion to Christianity, allowed his Christian marriage to exist celebrated in his chemical compound.[iii]

Linguistic communication choice [edit]

Achebe wrote his novels in English because the written standard Igbo language was created by combining various dialects, creating a stilted written form. In a 1994 interview with The Paris Review, Achebe said, "the novel form seems to get with the English language. In that location is a problem with the Igbo language. It suffers from a very serious inheritance which it received at the beginning of this century from the Anglican mission. They sent out a missionary past the proper name of Dennis. Archdeacon Dennis. He was a scholar. He had this notion that the Igbo language—which had very many different dialects—should somehow manufacture a uniform dialect that would be used in writing to avoid all these different dialects. Because the missionaries were powerful, what they wanted to exercise they did. This became the law. Just the standard version cannot sing. In that location's nothing you can do with it to make information technology sing. It'due south heavy. It's wooden. It doesn't get anywhere."[4]

Achebe's pick to write in English has caused controversy. While both African and non-African critics concord that Achebe modelled Things Fall Autonomously on archetype European literature, they disagree nigh whether his novel upholds a Western model, or, in fact, subverts or confronts information technology.[5] Achebe continued to defend his decision: "English is something you spend your lifetime acquiring, so it would be foolish not to utilise it. Also, in the logic of colonization and decolonization it is actually a very powerful weapon in the fight to regain what was yours. English was the linguistic communication of colonization itself. It is non but something you use because you have it anyway."[6]

Achebe is noted for his inclusion of and weaving in of proverbs from Igbo oral culture into his writing.[7] This influence was explicitly referenced by Achebe in Things Autumn Apart: "Among the Igbo the art of conversation is regarded very highly, and proverbs are the palm-oil with which words are eaten."

Literary significance and reception [edit]

Things Fall Apart is regarded every bit a milestone in African literature. It has come to exist seen equally the archetypal modern African novel in English,[3] [six] and is read in Nigeria and throughout Africa. Information technology is studied widely in Europe, India, and North America, where it has spawned numerous secondary and tertiary analytical works. Information technology has achieved similar condition and repute in Australia and Oceania.[viii] [3] Considered Achebe's magnum opus, information technology has sold more than than xx million copies worldwide.[nine] Time magazine included the novel in its Time 100 Best English-language Novels from 1923 to 2005.[10] The novel has been translated into more than 50 languages, and is oftentimes used in literature, earth history, and African studies courses across the world.

Achebe is now considered to be the essential novelist on African identity, nationalism, and decolonization. Achebe'southward master focus has been cultural ambiguity and contestation. The complexity of novels such every bit Things Fall Apart depends on Achebe'south ability to bring competing cultural systems and their languages to the same level of representation, dialogue, and contestation.[6]

Reviewers have praised Achebe'southward neutral narration and accept described Things Fall Apart every bit a realistic novel. Much of the critical discussion about Things Autumn Apart concentrates on the socio-political aspects of the novel, including the friction between the members of Igbo society every bit they confront the intrusive and overpowering presence of Western government and beliefs. Ernest Due north. Emenyonu commented that "Things Autumn Apart is indeed a classic report of cross-cultural misunderstanding and the consequences to the balance of humanity, when a belligerent civilization or civilization, out of sheer arrogance and ethnocentrism, takes it upon itself to invade another civilisation, another culture."[11]

Achebe's writing about African society, in telling from an African betoken of view the story of the colonization of the Igbo, tends to extinguish the conception that African culture had been fell and primitive. In Things Fall Apart, western culture is portrayed as being "big-headed and ethnocentric," insisting that the African culture needed a leader. As information technology had no kings or chiefs, Umuofian culture was vulnerable to invasion past western civilization. It is felt that the repression of the Igbo language at the end of the novel contributes greatly to the destruction of the civilization. Although Achebe favours the African culture of the pre-western lodge, the author attributes its destruction to the "weaknesses within the native construction." Achebe portrays the culture as having a religion, a government, a system of money, and an creative tradition, as well as a judicial arrangement.[12]

Influence and legacy [edit]

The publication of Achebe'southward Things Fall Apart helped pave the way for numerous other African writers. Novelists who published after Achebe were able to find an eloquent and effective mode for the expression of the particular social, historical, and cultural situation of modernistic Africa.[5] Before Things Fall Autonomously was published, most of the novels about Africa had been written past European authors, portraying Africans equally savages who were in demand of western enlightenment.

Achebe broke from this outsider view, by portraying Igbo society in a sympathetic light. This allows the reader to examine the effects of European colonialism from a different perspective.[5] He commented: "The popularity of Things Autumn Autonomously in my own society can be explained merely ... this was the get-go fourth dimension nosotros were seeing ourselves, equally democratic individuals, rather than half-people, or every bit Conrad would say, 'rudimentary souls'."[6] Nigerian Nobel laureate Wole Soyinka has described the work as "the start novel in English which spoke from the interior of the African character, rather than portraying the African as an exotic, as the white man would encounter him."[thirteen]

The linguistic communication of the novel has not only intrigued critics but has too been a major gene in the emergence of the mod African novel. Because Achebe wrote in English, portrayed Igbo life from the point of view of an African man, and used the linguistic communication of his people, he was able to greatly influence African novelists, who viewed him as a mentor.[6]

Achebe's fiction and criticism continue to inspire and influence writers around the globe. Hilary Mantel, the Booker Prize-winning novelist in a vii May 2012 article in Newsweek, "Hilary Mantel's Favorite Historical Fictions", lists Things Autumn Apart as one of her 5 favourite novels in this genre. A whole new generation of African writers – Caine Prize winners Binyavanga Wainaina (current director of the Chinua Achebe Centre at Bard College) and Helon Habila (Waiting for an Angel [2004] and Measuring Fourth dimension [2007]), too every bit Uzodinma Iweala (Beasts of No Nation [2005]), and Professor Okey Ndibe (Arrows of Pelting [2000]) count Chinua Achebe every bit a significant influence. Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, the author of the popular and critically acclaimed novels Purple Hibiscus (2003) and Half of a Yellow Sun (2006), commented in a 2006 interview: "Chinua Achebe volition always be important to me because his piece of work influenced not so much my style as my writing philosophy: reading him emboldened me, gave me permission to write about the things I knew well."[6]

Things Fall Apart was listed by Encyclopædia Britannica every bit i of "12 Novels Considered the 'Greatest Book Always Written'".[14]

The 60th anniversary of the commencement publication of Things Autumn Apart was celebrated at the S Bank Centre in London, United kingdom, on 15 Apr 2018 with live readings from the book by Femi Elufowoju Jr, Adesua Etomi, Yomi Sode, Lucian Msamati, Jennifer Nansubuga Makumbi, Chibundu Onuzo, Ellah Wakatama Allfrey, Ben Okri, and Margaret Busby.[15] [16]

On November five, 2019, the BBC News listed Things Autumn Apart on its list of the 100 virtually influential novels.[17]

Film, telly, music and theatrical adaptations [edit]

A radio drama chosen Okonkwo was made of the novel in April 1961 by the Nigerian Broadcasting Corporation. It featured Wole Soyinka in a supporting role.[eighteen]

In 1970, the novel was made into a film starring Princess Elizabeth of Toro, Johnny Sekka and Orlando Martins past Francis Oladele and Wolf Schmidt, executive producers Hollywood lawyer Edward Mosk and his wife Fern, who wrote the screenplay. Directed by Jason Pohland.[19] [Flimportal 1]

In 1987, the volume was made into a very successful miniseries directed by David Orere and broadcast on Nigerian television by the Nigerian Television Authority. It starred several established moving-picture show actors, including Pete Edochie, Nkem Owoh, and Sam Loco Efe.[20]

In 1999, the American hip-hop band The Roots released their fourth studio album Things Fall Apart in reference to Achebe's novel. A theatrical production of Things Fall Autonomously, adapted past Biyi Bandele, took place at the Kennedy Center that yr as well.[21]

In 2019, the lyrics of "No Holiday for Madiba", a vocal honoring Nelson Mandela include the phrase, "things fall apart", in reference to the book'southward championship.

Publication information [edit]

- Achebe, Chinua. The African Trilogy. (London: Everyman'due south Library, 2010) ISBN 9781841593272. Edited with an introduction by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie. The book collects Things Fall Apart, No Longer at Ease, and Pointer of God in one volume.

See also [edit]

- Heart of Darkness

References [edit]

- ^ Irele, F. Abiola, "The Crisis of Cultural Memory in Chinua Achebe's Things Fall Apart", African Studies Quarterly, Volume 4, Issue iii, Autumn 2000, pp. 1–forty.

- ^ Smuthkochorn, Sutassi (2013). "Things Autumn Apart". Journal of the Humanities. 31: 1–ii.

- ^ a b c d Kwame Anthony Appiah (1992), "Introduction" to the Lowest's Library edition.

- ^ Brooks, Jerome, "Chinua Achebe, The Art of Fiction No. 139", The Paris Review No. 133 (Wintertime 1994).

- ^ a b c Booker (2003), p. 7.

- ^ a b c d e f Sickels, Amy. "The Critical Reception of Things Fall Apart", in Booker (2011).

- ^ Jayalakshmi 5. Rao, Mrs A. 5. N. College, "Proverb and Culture in the Novels of Chinua Achebe", African Postcolonial Literature in English.

- ^ admin (2015-xi-16). "Chinua Achebe". BOOK OF DAYS TALES . Retrieved 2020-10-18 .

- ^ THINGS Fall Apart by Chinua Achebe | PenguinRandomHouse.com.

- ^ "All-Time 100 Novels| Total list", Time, 16 October 2005.

- ^ Whittaker, David, "Chinua Achebe's Things Fall Apart", New York, 2007, p. 59.

- ^ Achebe, Chinua (1994). Things Fall Apart. London: Penguin Books. pp. 8. ISBN0385474547.

- ^ The Periodical of Blacks in Higher Didactics 2001, pp. 28–29.

- ^ Hogeback, Jonathan, "12 Novels Considered the 'Greatest Volume E'er Written'", Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ^ Murua, James, "Chinua Achebe'southward 'Things Autumn Apart' at 60 celebrated", James Murua's Literature Weblog, 24 April 2018.

- ^ Hewitt, Eddie, "Brnging Achebe's Masterpiece to Life", Brittle Paper, 24 April 2018.

- ^ "100 'most inspiring' novels revealed by BBC Arts". BBC News. 2019-11-05. Retrieved 2019-11-10 .

The reveal kickstarts the BBC'southward year-long celebration of literature.

- ^ Ezenwa-Ohaeto (1997). Chinua Achebe: A Biography Bloomington: Indiana University Press, p. 81. ISBN 0-253-33342-three.

- ^ David Chioni Moore, Analee Heath and Chinua Achebe (2008). "A Conversation with Chinua Achebe". Transition. 100 (100): 23. JSTOR 20542537.

- ^ "African movies direct and amusement online". world wide web.africanmoviesdirect.com . Retrieved 10 Dec 2017.

- ^ Triplett, William (1999-02-06). "1-Dimensional 'Things'". Washington Post . Retrieved 2020-09-fourteen .

- Grouped References

- ^ Filmportal. "Things Autumn Apart".

Sources [edit]

- "Chinua Achebe of Bard College". The Journal of Blacks in Higher Educational activity. 33 (33): 28–29. Autumn 2001. doi:10.2307/2678893. JSTOR 2678893.

Further reading [edit]

- Achebe, Chinua. Things Fall Apart. New York: Anchor Books, 1994. ISBN 0385474547

- Baldwin, Gordon. Strange Peoples and Stranger Customs. New York: W. W. Norton and Company Inc, 1967.

- Booker, M. Keith. The Chinua Achebe Encyclopedia. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 2003. ISBN 978-0-325-07063-6

- Booker, Thousand. Keith. Things Autumn Apart, by Chinua Achebe [Disquisitional Insights]. Pasadena, Calif: Salem Press, 2011. ISBN 978-1-58765-711-v

- Frazer, Sir James George. The Gilt Bough: A Report in Magic and Religion. New York: The Macmillan Company, 1942.

- Girard, Rene. Violence and the Sacred. Trans. Patrick Gregory. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Academy Press, 1977. ISBN 0-8018-1963-6

- Islam, Md. Manirul. Chinua Achebe'south 'Things Fall Apart' and 'No Longer at Ease': Critical Perspectives. Deutschland: Lambert Bookish Publishing, 2019. ISBN 978-620-0-48315-7

- Rhoads, Diana Akers (September 1993). "Civilization in Chinua Achebe'due south Things Autumn Apart". African Studies Review. 36(2): 61–72.

- Roberts, J. M. A Short History of the Earth. New York: Oxford Academy Press, 1993.

- Rosenberg, Donna. World Mythology: An Anthology of the Great Myths and Epics. Lincolnwood, Illinois: NTC Publishing Group, 1994. ISBN 978-0-8442-5765-five

External links [edit]

- Chinua Achebe discusses Things Fall Apart on the BBC World Book Lodge

- Teacher's Guide at Random House

- A "New English" in Chinua Achebe's Things Fall Autonomously

- Study Resource for writing nearly Things Autumn Autonomously

- Study guide

- Words nowadays in the novel used in past SATs. Includes definitions, words in order from the volume, and iii different tests.

- Things Fall Apart Reviews

- Things Fall Apart on Wiki Summaries

- Things Fall Autonomously study guide, themes, analysis, teacher resources

- Things Fall Apart Igbo Culture Guide, Igbo Proverbs

- Things Fall Autonomously Summary

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Things_Fall_Apart

0 Response to "In Achebeã¢â‚¬â„¢s Things Fall Apart, What Best Describes the Way Okonkwo Treats His Family?"

Post a Comment