Why Does Horse Become Poor Again

Refeeding the Poorly Conditioned Horse

By Kris Hiney, Lyndi Gilliam

- Jump To:

- Assessing Body Condition

- Review of Published Reports on Refeeding Poor Conditioned Horses

- Suggested Feeding Plans for Reconditioning Poor Conditioned Horses

- Body Condition Scores

Poor body status in horses can be acquired past many factors. Age, disease and lack of acceptable nutrition are 3 of the most common. Usually, nutritional related reasons are due to a lack of carbohydrate, fat or protein intake. Even so, even with appropriate care and nutrition, elderly horses may not exist able to maintain a desired torso condition. Similarly, numerous diseases can pb to poor body condition, from a lack of ambition, or the inability of the horse's trunk to part usually.

A refeeding plan coordinates nutritional and veterinarian therapies that combine to improve torso condition of a poorly conditioned horse. Successfully refeeding a poorly conditioned horse can be extremely difficult, even with knowledgeable supervision and a detailed, well-referenced plan. One veterinary science study reported that nine of 45 horses that had previously been subjected to prolonged malnutrition died after existence placed with a responsible caregiver and provided an appropriate diet.i Defining a refeeding programme requires in-depth diagnosis of the health status of the horse. Veterinarian intervention, therefore, is necessary prior to and during the refeeding period of poorly conditioned horses. Typically, veterinarians will perform concrete examinations that include a detailed dental examination and subsequent diagnostic tests to evaluate concerns noted during physical examinations.

Assessing Body Condition

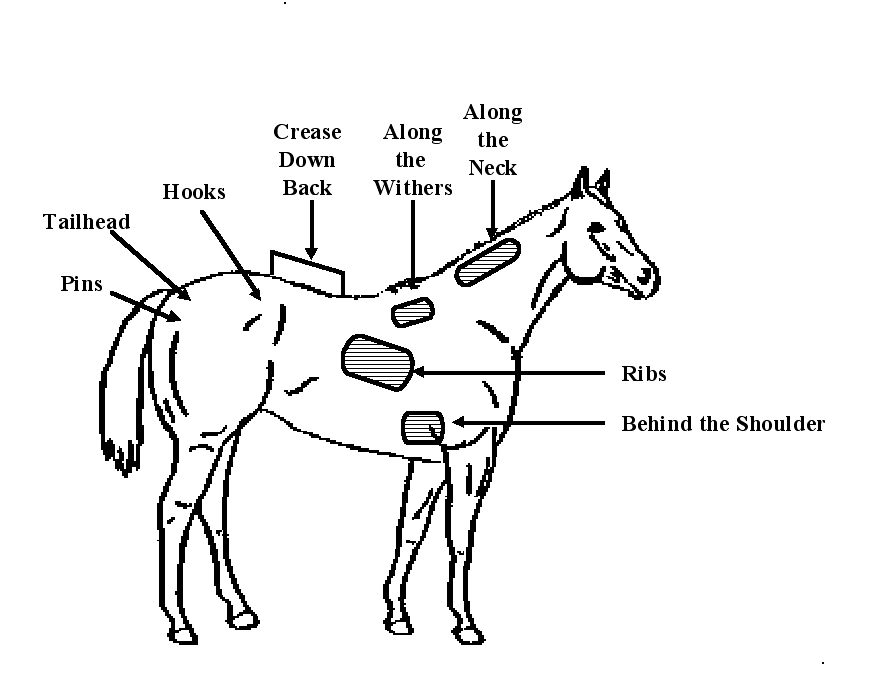

Body condition relates to the corporeality of visible fatty cover on a horse's body. The well-nigh commonly accustomed cess method is a scoring system using a scale of ane to 92. A thorough explanation of the scoring organization is discussed in OSU Extension Fact Canvas F-3920 Torso Condition of Horses. Figure one defines the locations on a horse's torso that have observable differences of fatty cover at dissimilar body conditions. Horses in the low end of the condition scale have trivial noticeable fat comprehend at locations along the neck, behind the withers, along the ribs and on the hip. The individual bony structures of vertebra and the pelvis are noticeable (Photos 1 and 2).

Effigy 1. Locations of Fat Encompass used in Body Condition Scoring System.

Effigy ii. Equus caballus in a body condition score ane. Note skeletal features evident in areas of normal fat deposition. Photo courtesy of Dr. Don Henneke, Tarleton Land University.

Effigy 3. Horse in torso condition score of ii. Note the evidence of individual vertebra along the dorsum and croup surface area.

Horses in poor to very sparse torso conditions (Scores of i or ii) have little visible fat and announced to have had appreciable lean tissue degradation. Body fat provides the major free energy reservoir. The horse'south body systems will mobilize fat for fuel when free energy needs are greater than the daily energy intake. As the time period of inadequate nutrition is prolonged, fatty stores are depleted and noticeable amounts of muscle are cleaved down for utilize as energy.

There is no uniformly agreed upon benchmark as to what constitutes a horse in undesirably low body condition. It is mutual for some highly trained equine athletes to have thin to moderately sparse body conditions and be in the elevation of health. More often than not, most reports from veterinarians and nutritionists consider horses in body condition scores of one or two as emaciated, malnourished, or under conditioned as a consequence of beingness underfed or combating a illness or age condition that restricts weight gain.

Poor torso condition is usually associated with bereft intake of free energy or protein. Malabsorption, parasitic infestation, onetime historic period, senility, and a number of diseases can too cause emaciation. Thus, to exist constructive, nutritional therapies for correcting poor body condition must be aligned with the correct diagnosis of the cause and the health condition of the horse.

Review of Published Reports on Refeeding Poor Conditioned Horses

Some poor conditioned horses may be so dehabilitated that they are unable or lack the desire to swallow. Horses in this status will crave veterinary intervention. A feeding tube tin can exist placed into a horse'south stomach so a liquid diet can be administered if a horse is unable or unwilling to swallow. Placing a nasogastric tube into a horse's stomach should exist performed by a veterinary equally an improperly placed tube tin can result in death. An intravenous catheter can supply nutritional support if a horse'due south digestive tract cannot handle liquid or solid food. This type of nutrition is costly and is only used short term until the digestive tract will accept and utilize feed.

The feeding frequency, dietary food contour, and physical form of the diet will define the refeeding plan. Although limited in both number and scope, at that place are reports in veterinary and nutritional science journals that provide guidance for refeeding plans. The rations recommended in specific reports probable are influenced by the availability of specific feeds and processing methods at the time and location of the report, regional traditions of what routinely is fed, and personal feel. As such, the specific ingredients mentioned may not be equally important every bit are similarities of food composition and routines amongst the reports.

In general, information technology is recommended to provide grain post-obit one or two days later feeding long stem forage. Grains are relatively loftier in starchy carbohydrates, and there is some concern among veterinarians and nutritionists that horses in poor condition may non utilize these ingredients initially with as much success as high fiber feedstuffs. Recommendations are to begin refeeding by starting with water, electrolytes, and in most cases, hay, followed with frequent meals of pocket-size amounts of grain.3,4,5

1 suggested protocol is to begin with offerings of small amounts of hay, i.due east. two pounds every two hours3. After several meals, amounts are increased to levels approximating virtually 1 one-half the needs for dietary free energy for maintenance by feeding hay in iv meals per day for 2 days. Hay is so offered free choice.

This diet should continue for a couple of weeks, after which additional nutrient sources, i.e. grains, are introduced. Similar to hay, grains should be introduced gradually by initially feeding small amounts at frequent intervals.

One such recommendation is to innovate grain by apportioning into five to vi daily feedings of ane pound to one and one half pounds each.4This level should be tolerated well by most averaged sized stock horses. Yet, recommendations emphasized the need to treat horses individually, and suit rationing frequency and levels co-ordinate to the horse'due south response.

A different report provides another routine for introduction of a grain mix.v Horses in extremely poor condition are to be offered hay and water if they are initially unable to walk, along with initial diets prescribed past a veterinarian. Once stabilized, a 12 percent crude protein grain mix with mineral supplement, molasses, and bran is prescribed to be fed iii times daily at levels of about ane pound per feeding. Afterwards 1 week, the levels are increased to ii pounds per feeding for the a.m. and p.m. feedings, with the noon feeding remaining at 1 lb. Once the horse has improved its status somewhat, the grain mix is to be fed at levels of three to 9 pounds per day, depending on the size of the equus caballus. The horse continues to receive gratis option levels of hay and unlimited access to grazing. After 30 days of feeding, zero to xvi pounds of the grain mix is fed daily into 2 allotments each day. The estimated fourth dimension period to improve body condition from a very poor condition to a moderate condition is half dozen to 10 months.

A 2004 report from the College of Veterinarian Medicine at the Academy of Minnesota provides a refeeding protocol based on their experiences of treating poor conditioned horses.6 A systematic protocol is outlined that includes monitoring of weight, physical examinations, parasite treatment, and blood chemistry profiles. The dietary protocol begins with restricted intake of high quality grass hay. Hay is offered by paw at hourly intervals for the first mean solar day if horses had no oral intake for the previous twenty-four hours. If the horse had some feed earlier admission, it was permitted full access to grass hay.

A complete feed is gradually introduced start on the fourth day at one half pound per meal twice daily for an average size horse. A complete feed is formulated to incorporate all nutrients needed in the diet of a horse in a processed mix, and does not require the addition of hay for balancing nutrient needs. The amount or frequency of feeding the complete feed is increased gradually every other solar day to a maximum of three pounds per feeding equally long every bit the horses are consuming the allotted amount. Trace minerals are added in block or loose form beginning on the 4th day.

Twelve horses receiving this protocol reported weight gain that varied greatly from horses showing little to no gain to some gaining equally much equally six to 7 pounds per day for xi days. These loftier levels of gain per day are likely to exist reflective of trunk fill up of forage and water in the digestive tract. Rates of gain of bodily tissue may exist more in the range of ane to three pounds of gain per day during the initial refeeding period. Body condition scores averaged a score of two with a range of one to three. Body weights ranged from approximately 400 to 1,100 pounds and ages from five months to over 20 years.

Well-nigh reports, every bit those above, have made recommendations based on clinical experience and review of example studies instead of controlled research studies that accurately quantify the response of undernourished horses to different diets. 1 trial that has conducted such research has been reported by investigators at the School of Veterinary Medicine at University of California, Davis.7 Xx-two poorly conditioned horses were divided into three groups. The previous histories of the horses were unknown. On average, the horses weighed about 700 pounds, between 14 and 15 hands tall, and in a body score of one or two.

The groups differed in the type of nutrition: alfalfa hay, oat hay, or a third diet made of a combination of oat hay with a commercially available, complete feed containing grain and loftier cobweb components. The equus caballus'south physiological response to the initial x days of refeeding were observed and compared.

The three different diets were fed at equal levels of free energy intake. For the first three days, the horses were fed six times per solar day at levels estimated to provide l percent of their normal digestible energy requirements. This equated daily to six to seven pounds of alfalfa hay, almost nine pounds of oat hay, or vii pounds of the oat hay with the complete feed. Amounts were increased to estimated levels of 75 percent of their normal digestible free energy requirements for the following two days, so increased to 100 percent of their estimated digestible energy requirements for the last 5 days of the investigation. The number of meals fed was reduced from 6 to four times per day during days six through ten. Total intake on day ten averaged nigh 13 pounds of alfalfa, 17 pounds of oat hay, or thirteen pounds of the oat hay-consummate feed mix.

Weight gains were not different between the three groups of horses, although alfalfa hay was suggested to have several advantages. The oat hay was very bulky and caused diarrhea in several horses, and the oat hay was lower in some essential minerals. The authors cautioned confronting the initial employ of the higher starch-containing ration of the oat hay combined with a complete feed because of prove suggesting the potential for agin blood insulin responses. An undesirable insulin response to the initial period of refeeding is i of the noted concerns with researchers studying the effects of reintroducing food post-obit prolonged malnutrition.

The same researchers after compared alfalfa hay with an alfalfa hay combined with corn oil8. The addition of corn oil reduced the amount of hay needed to be fed at comparable estimated digestible free energy intakes. While the addition of corn oil had no harmful effects, the investigators however recommended the alfalfa hay without corn oil. More hay was fed without the addition of corn oil, which increased the intake of minerals contained in the hay.

Regardless of diet composition, the researchers emphasized the need for small, frequent allotments of food existence offered in the initial refeeding period. They recommended that horses can be fed as much as they will consume of an alfalfa hay nutrition after x days to two weeks. Although some weight gain can be expected after ane month of intendance, they suggested that three to 5 months volition exist necessary for the horses to return to normal body weight.

Suggested Feeding Plans for Reconditioning Poor Conditioned Horses

Several recommendations for the initial refeeding of poor conditioned horses tin be adult from the suggestions and enquiry discussed above. A concrete examination including careful examination of the oral cavity and appropriate diagnostic tests should be performed past a veterinarian so nutritional plans can exist aligned with the health status of the horse. It is possible that appetite or ability to eat solid feed may be compromised. In that case, supportive liquid diets may exist prescribed past a consulting veterinarian.

Water should exist offered and intake documented. The almost mutual form is to feed hay or coarsely processed provender for the first several days. Fodder should exist of high quality, and alfalfa is recommended as one suitably desired provender type. If hay is not available, alfalfa cubes may be an alternative. Softening cubes past soaking in water may be necessary if the equus caballus'southward dental condition is poor. Indigestible, beefy, poor quality forage is not recommended because of its poor digestibility and lower levels of nutrients.

High quality pastures can be used as the initial source of nutrition. Intake patterns should be observed to ensure horses are eating. Restricting horses to limited grazing may exist necessary on pastures with moderate to lush vegetation. In these situations, turning horses to pasture 3 to four times a day for one or two hours is a logical starting point.

Grains tin can be introduced into the feeding program afterwards using forage for the first several days. By doing and then, horses are consuming most of the intake of carbohydrate as fiber rather than starch. However, note that not all processed feeds are high in starch. Soyhull pellets, alfalfa repast pellets, or other high fiber by-products may be a logical alternative to long stem forage if lower starch, college fiber rations are desired.

Grains will provide a more full-bodied source of useable energy equally compared to a high fiber feed because starch will be more digestible than fiber. Equally such, it is advantageous to introduce grains shortly afterward the initial refeeding menses of i to four days. Grains should exist fed in several small meals per 24-hour interval, and amounts gradually increased to levels typical of horses of similar size and weight when in moderate status. Feeding amounts for a 900 to 1,000 pound horse can beginning at one to 2 pounds of grain per twenty-four hour period for the first two to four days, and increased to twice that amount by 7 to ten days. Feeding frequency of grain tin can exist reduced to ii to three times per solar day sometime during the second week of feeding. Horses should be monitored closely for signs of laminitis or founder. These conditions are evidenced by reluctance to move, walking very gingerly or tenderly, increased time spent lying down, or rocking back on the hind legs earlier moving the front end legs. A veterinarian should exist contacted immediately when whatsoever of these signs are observed.

There are differences in the food content of commercially prepared concentrate feeds. Some mixes take large amounts of fiber added to a grain, and are labeled as complete feeds. These mixes can substitute the demand for provender more than so than mixes containing larger amounts of college starch containing ingredients. These feeds will usually have increased fatty levels by inclusion of plant oil to the mix. Supplying supplemental oil as role of the processed mix, or supplementing grain mixes and pelleted high cobweb feeds by topdressing an oil, has the advantage of increasing the energy density of the feed. Vegetable oil contains much more free energy per weight as compared with high carbohydrate, depression fat feeds.

There is little information as to determining the need for increasing levels of protein higher up amounts normally recommended to be fed to horses of like size. Still, poly peptide tissue may accept been broken downwards, thus requiring a demand for protein growth during refeeding. As such, it is logical to suggest protein requirements are increased to correspond levels more characteristic of younger horses in similar growth. Increasing the suggested requirement for crude protein by nearly 20 percent in a higher place normal maintenance levels may better see needs during initial refeeding of poor conditioned horses. Equally an example, a 1,000 pound equus caballus may require approximately 1.25 pounds of rough protein in maintenance conditions. When refeeding a poor conditioned equus caballus of like size, requirements for crude protein may increase to 1.5 pounds of crude protein per day. To determine the poly peptide intake of a horse, the amount of ration by weight is multiplied by the pct crude protein of the ration. For example, a equus caballus consuming an all alfalfa hay ration, which is 20 percent crude poly peptide at levels of 10 pounds per mean solar day, would be consuming two pounds of crude protein.

Similar adjustments to minerals and vitamins could be assumed for similar reasons when refeeding a poor conditioned equus caballus. As such, grains and complete feeds formulated for horses in growth may have advantages of use for refeeding as compared to formulations with fewer nutrients per pound intended for horses at maintenance.

Full intake of feed will exist express to the equus caballus'due south level of appetite and the maximum voluntary intake. In about situations, horses will voluntarily consume as much equally 3 percentage of body weight per 24-hour interval in nutrition dry matter. While the dry matter of pasture can vary greatly, most grains and hays are almost 90 percentage dry affair. For instance, a i,000 pound horse may be expected to consume as much as 30 to 35 pounds of hay per day voluntarily. In some situations, the ambition of the horse volition restrict voluntary intake to levels much lower than normal when the horse is in poor condition. Also, a grain mix volition likely be combined with hay when refeeding poor conditioned horses. The add-on of a higher energy feed will decrease the need to feed rations at maximum levels of voluntary intake.

Accurately assessing improvement is important. Initial body weight and weight proceeds should be recorded. Weigh tapes can be used if big animal scales are unavailable. Weight gain is expected to exist highly variable betwixt horses. Initial weight gains of one to two pounds per twenty-four hours would be expected for favorably responding horses with a body weight between 900 and i,000 pounds. Significant weight gains sufficient to modify trunk status score will have a minimum of several weeks. Also, veterinary assessment of health should be routinely scheduled as part of the refeeding plan.

Related wellness factors, degree of emaciation, and the horse's response to refeeding volition direct the refeeding program, so apply the suggestions as a general guide. Besides, comprise general feeding management guidelines used for good for you horses as described in OSU Extension Fact Sheet F-3973 Feeding Management of the Equine.

Trunk Status Scores

- Poor. Fauna extremely emaciated. Spinous processes (portion of the vertebra of the backbone which projection upward), ribs, tailhead, and bony protrusions of the pelvic girdle (hooks and pins) projecting prominently. Bone structure of withers, shoulders, and neck are easily noticeable. No fat tissues can be felt.

- Very Thin. Animal emaciated. Slight fat covering over base of spinous processes and transverse processes (portion of vertebrae which projection outward) of lumbar (loin expanse) vertebrae experience rounded. Spinous processes, ribs, shoulders, and neck structures are faintly discernible.

- Thin. Fat built up most halfway on spinous processes, transverse processes cannot be felt. Slight fat cover over ribs. Spinous processes and ribs are hands discernible. Tailhead prominent, just individual vertebrae cannot exist visually identified. Hook bones (protrusion of pelvic girdle actualization in upper, forward part of the hip) appear rounded, but are easily discernible. Pin bones (bony projections of pelvic girdle located toward rear, mid-department of the hip) not distinguishable. Withers, shoulders, and cervix accentuated.

- Moderately Thin. Negative crease along back (spinous processes of vertebrae protrude slightly above surrounding tissue). Faint outline of ribs discernible. Tailhead prominence depends on conformation, fatty tin can be felt around it. Hook bones are not discernible. Withers, shoulders, and neck are not plainly thin.

- Moderate. Back level. Ribs cannot be visually distinguished, but can be easily felt. Fat around tailhead beginning to feel spongy. Withers appear rounded over barbed processes. Shoulders and neck blend smoothly into body.

- Moderate to Fleshy. May have slight crease downwardly dorsum. Fat over ribs feels spongy. Fat round tailhead feels soft. Fat beginning to be deposited along the sides of the withers, behind the shoulders, and along sides of neck.

- Fleshy. May take crease downwards back. Private ribs can be felt, but noticeable filling betwixt ribs with fat. Fat around tailhead is soft. Fat deposited along withers, backside shoulders, and along cervix.

- Fatty. Crease downwardly dorsum. Hard to feel ribs. Fat effectually tailhead very soft. Expanse along withers filled with fat. Area behind shoulder filled in flush. Noticeable thickening of neck. Fat deposited forth inner buttocks.

- Extremely fatty. Obvious crease down back. Patchy fat actualization over ribs. Bulging fat around tailhead, along withers, behind shoulders, and along neck. Fatty along inner buttocks may rub together. Flank filled in flush.

iWhiting, T. L., R. H. Salmon, and One thousand. C. Wruck. 2005. Chronically starved horses: predicting survival, economical, and upstanding considerations.Tin. Vet. J. 46(4): 320-324.

2Henneke, D. R., G. D. Potter, J. Fifty. Kreider, and B. F. Yeates. 1983. Human relationship betwixt condition score, physical measurements, and trunk fatty percentage in mares.Equine Vet. J. 1983 fifteen(4):371-372.

threeKronfeld, D. S. 1993. Starvation and malnutrition of horses: recognition and treatment. J. Equine Vet. Sci. thirteen(five):298-303.

4Finnocchio, E. J. 1994. Equine Starvation: Recognition and rehabilitation of the recumbent, malnourished horse.Large Brute Veterinary: March/April, pgs six-10.

5Poupard, D. B. 1993. Rehabilitation of horses suffering from malnutrition.J. Equine Vet. Sci. 13(five):304-305.

6Wilson, J.H. and D.A. Fitzpatrick. 2004. How to manage starved horses and finer work with humane and law enforcement officials. 50th AAEP Proc., p. 428-432.

sevenWitham, C. 50., and C. L. Stull. 1998. Metabolic responses of chronically starved horses to refeeding with three isoenergetic diets.JAVMA 212(5):691-696.

viiiStull, C. 2003. Nutrition for rehabilitating the starved horse.J. Equine Vet. Sci. 23(10):456-457.

Kris Hiney

Extension Equine Specialist

Department of Animal Scientific discipline

Lyndi Gilliam, DVM, DACVIM

Equine Internal Medicine Veterinarian

Eye for Veterinarian Health Sciences

Was this information helpful?

YESNO

Source: https://extension.okstate.edu/fact-sheets/refeeding-the-poorly-conditioned-horse.html#:~:text=Poor%20body%20condition%20in%20horses,carbohydrate%2C%20fat%20or%20protein%20intake.

0 Response to "Why Does Horse Become Poor Again"

Post a Comment